National Review, April 11, 1986

By Peter Paluch

ASIDE FROM the climate, the 28th International Film & TV Festival of New York was as lush and glamorous as any Hollywood bash. The festival is one of the most highly regarded in the world, with 44 countries represented in 1985. The two thousand people seated for the awards-presentation banquet in the Imperial Ballroom of the Sheraton Centre hotel represented 5,313 entrants and the cream of the industry. The BBC, ABC, NBC, and CBS were there in force. So were HBO and Turner Broadcasting.

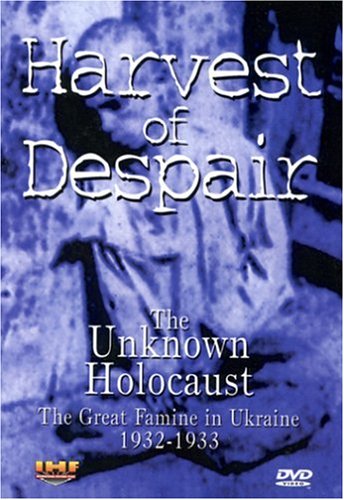

The gold medalist in the TV Documentaries category was announced halfway through the braised beef bordelaise – Harvest of Despair, a 55-minute Canadian production disinterring the story of the man-made Ukrainian famine buried half a century ago beneath layers of Soviet propaganda and Western venality. After the presentation of the gold medals in the ten categories included in the overall TV Entertainment Programs and Specials Group, it was time for the ice-cream log assorti in meringue crown and the announcement of the winner of the Grand Award Trophy Bowl. Again, it was Harvest of Despair, judged the “most outstanding entry” of all 837 films in the group. These two awards gave the film enough points in international competitions to make it eligible for an Oscar, although too late for this year’s Academy Awards.

This was last November 15. Ten months earlier, Peter Foges, Public Affairs Programming Director at New York’s PBS affiliate, WNET, was pressed to explain why he had rejected the film. After a long silence he replied that it was “technically deficient” and of “dubious quality,” and that it did not meet PBS’s “production standards.” Pressed for an explanation of what that meant, Foges stumbled for a moment and said, not entirely convinced himself, that the sound of horses’ hoofbeats should have been dubbed into a still scene showing human corpses being carted away. (Those effects are included.)

These two incidents typify the whipsaw reaction to an extended effort to call to the American media’s attention the untold story of how Soviet authorities deliberately starved to death at least seven million people in the traditional “breadbasket of Europe.” Harvard University’s Ukrainian Research Institute recently concluded a monumental three-year research project on the subject, headed by British Sovietologist Robert Conquest; the resulting book will be published this spring by the Oxford University Press. The Harvard project coincided with the production in Toronto of Harvest of Despair, a private effort that soon attracted the attention and support of the National Film Board of Canada. Independent of each other, the Canadian film and the Harvard study were simultaneous firsts concerning a subject that Harvard’s James Mace said “remains as the least understood cataclysm of this century, a tragedy that has disappeared from the public consciousness so completely that it represents the most successful example of the denial of genocide by its perpetrators.”

The importance and timeliness of the issue seemed obvious enough, and any one of the several threads in this story would make it a natural for broader dissemination.

There is most obviously the purely human-interest aspect–nothing less than the systematized murder of seven million human beings in less than a year, three million of them children under the age of seven. That is the conservative figure, extrapolated from Soviet statistics. That the actual number is significantly higher must be assumed, since the compilers of the first Soviet census after the famine was lifted were summarily shot for “undermining Socialism by deliberately undercounting the population.” A “correct” census was immediately prepared. It is on the “corrected” version that the seven-million figure is based. The true extent of the human cataclysm is perhaps more accurately suggested by Dr. W. Horsley Gantt, a British physician who was in the Soviet Union at the time and who relayed private estimates by Soviet officials of as many as 15 million killed, fully half the Ukrainian nation, and equal to the population of all of Central America today.

The novelty in all this is that the famine in Ukraine was modern history’s first example of “famine on command.” It was not brought about by drought, or crop activists, brought in for the task from Russia, physically removed virtually all of the food from the region. Dogs and cats vanished from the streets, as the state abruptly realized a need for their skins. The famine was the realization of Soviet Foreign Minister Maksim Litvinov’s dictum, “Food is a weapon.” It was also the precursor of starvation politics in Afghanistan and Ethiopia.

The second thread of the story, which the producers hoped the media half a century later would have the integrity to address, was the Western media’s responsibility for spiking the story originally in order to curry favor with the Kremlin. Among the luminaries of the time, Walter Duranty of the New York Times was the acknowledged dean of Western reporters in Moscow. He categorically denied the existence of any famine, prompting Stalin to compliment him – “You have done a good job in your reporting of the USSR” – and to reward his efforts with the Order of Lenin.

Pulitzer Journalism

THE PULITZER PRIZE Committee was of like mind and bestowed its own coveted award upon Duranty for his “dispassionate, interpretative reporting . . . marked by scholarship, profundity, impartiality, sound judgment, and exceptional clarity . . . excellent examples of the best type of foreign correspondence.” In order to promote such journalism, Duranty was permitted by Soviet authorities to accompany Litvinov on his triumphant trip to the United States, when we negotiated the diplomatic recognition of the USSR at the very height of the famine.

To be sure, a few European papers, such as France’s Le Matin, decided to publish the truth. But the American media were damningly silent, both about the genocide and about Soviet manipulation of the foreign press.

The third thread of the story is summed up in George Orwell’s observation, “We have now sunk to a depth at which the restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men.” It may sound tautological to repeat that “the Soviet Union” is not “Russia,” but it is nonetheless necessary to do so. The USSR is a multinational federation of formerly independent nations. It is not a monolithic state, any more than is any empire. An Uzbek in Samarkand or a Latvian in Riga has about as much similarity to, or affinity for, a Russian in Leningrad as does an Afghan in Kabul. In this light, the man-made famine in Ukraine speaks volumes about Moscow’s relationship with the non-Russian nations of the USSR, which account for 50 per cent of its population.

None of these issues has proved attractive to the media in the United States. At this writing Harvest of Despair has been shown only on two small U.S. television stations; and virtually no press attention has been given to the discoveries of the Conquest group. This has not been for lack of trying by either the Harvest producers or the Harvard Institute. But all their efforts have been met with the sort of embarrassingly inarticulate or silent rejection that suggests people are unwilling to explain their reasons for not doing the obviously right thing.

Thus, for instance, the three commercial television networks did not see fit to articulate any reason whatsoever for their rejection of the story. We have reason to believe that, at least in the case of one of the networks, a fawning concern, at the highest level, with maintaining the good graces of the Kremlin led to the network’s self-censorship.

The Harvard group hoped the release of Harvest of Despair might make a difference. A recognized film-distribution firm in Washington, D.C., viewed the film and expressed enthusiastic interest in serving as its exclusive agent in the United States and Canada. But after the firm discussed the matter with its industry contacts on the East and West Coasts, a wall of silence descended. No explanation. No replies to inquiries. Nothing.

Finally, after a ten-month blackout, and on the heels of WPBT’s rejection, the main office of PBS in Washington opined that the film presents only “one point of view” and that it is “subjective.”

Lost in America

PERHAPS THE strangest aspect of the story is the contrast between the silence of the media in the United States concerning Harvest of Despair and the critical acclaim elsewhere. In addition to its sweep in the international film competitions, the film has been lauded as “a searing 55-minute documentary,” “powerful,” “an eye-opener,” “an important film . . . it should be seen by everyone,” “an unquestionably sobering film which rightfully deserves wide distribution on television,” “A riveting account,” “a superb chronicle,” “un film eminemment necessaire.” CBC broadcast the film throughout Canada last September, and European, Australian, and Japanese rights are being negotiated.

The only important exception among the critics is the New York Times’s Vincent Canby. Writing on the occasion of the screening at the New York Film Festival last October 10, Canby defended the Times’s Walter Duranty. He did not deny that Duranty lied; he criticized the film for not explaining why Duranty did it. He excused Duranty’s perfidy by explaining (citing Harrison Salisbury) that Duranty was not a Communist ideologue but merely a “calculating careerist,” as if that were a valid defense for fraud.

Canby continued: Harvest of Despair was visually “full of generalities.” An astonishing statement. The New York Times first censors the printed news and then, fifty years later, complains that the visual record is too general. The remarkable thing is that there is any visual record extant in the West. (Shoah, the recent documentary of the Nazi Holocaust, was applauded by the critics even though it runs for nine and a half hours without using any archival footage.)

Canby ruled, ultimately, that Harvest of Despair is a “frankly biased, angry recollection” of a “hugely emotional subject.” “Biased” is a serious charge to hurl at a documentary. But what does it mean here? That the producers disapprove of genocide” Or that they twisted the facts to make genocide appear where there was none? If it was the latter, Canby gave not a single example, nor the slightest substantiation. A letter requesting substantiation remains unanswered.

What is to be made of the particular resistance of the U.S. media? The story is clear enough. After 15 years of trying, Moscow had been unable to solidify Communist rule in Ukraine, the largest non-Russian republic in the Soviet Union. Soviet reaction to Ukrainian opposition was simple – starve the opponents. A quarter, perhaps half, of the population was driven to madness, cannibalism, and death. During the whole process, Moscow was able to muzzle the Western media, enthrall Western intellectuals, and entrance Western governments. For half a century the story remains entombed. Then, a major university study and an award-winning film expose the genocide and its cover-up, and the U.S. media do not respond. Why?

Lap Dogs of the Press

AS ONE OF the few Western journalists who remained true to his public trust, Malcolm Muggeridge wrote at the time that “the man-made famine in Ukraine is one of the most monstrous crimes in history, so terrible that people in the future will scarcely be able to believe it ever happened”. But, of the myriad excuses given by the American media, disbelief was never even intimated. Nor would we expect to see the line of demarcation between belief and disbelief to be so sharply drawn between the United States on the one hand, and Canada, Western Europe, and Australia on the other. Quite beyond Harvest, over the last three years, the famine itself has been the focus of extensive editorial and reader discussion in the major publications of those countries.

Part of the reason must surely lie in the American media’s refusal publicly to admit to its especially disgraceful delinquency. But the ultimate reasons can only be the same ones that prompted the media to spike the story in the first instance. One of those is a fawning concern to maintain their good standing with the Kremlin. An indirect example of this is found in the Wall Street Journal, which does not maintain an office in Moscow and whose editorial policy has earned Moscow’s ire. Moscow thus has no leverage on the Journal, and the Journal has publicized the direct connection between the man-made famine in Ukraine and present-day developments in Afghanistan and Ethiopia.

The other, more important reason is the pervasiveness of the very political bias that PBS was so quick to ascribe to Harvest of Despair. It isn’t simple conscious complicity, but unknowing gullibility, that is behind the acceptance of Soviet horrors. Because this bias is often subliminal, it is all the more insidious. David Satter wrote in the October 22, 1985, Wall Street Journal: “The Soviet authorities understand that concessions to their view of reality weaken an adversary’s ability to insist on the absolute value of anything. This is why the effort to induce the world to take their ideological lying literally is not just a question of prestige for the Soviet leaders but also a matter of political strategy. The Soviet authorities do not expect Western journalists to believe Soviet propaganda, but only to repeat it uncritically, without any effort to analyze what it means, so that, over time, the Soviet Union’s ideological lying and officially sanctioned misuse of language, enhanced by the credibility of important American publications, begin to have the same numbing effect on Westerners as on Soviet citizens.”

Were, say, ABC to air Harvest of Despair or its own documentary on the subject, it would freeze for an hour the Soviet phantasmagoria. The new image: The famine in Ukraine was not the unfortunate but unintended by-product of the overall collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union, as soporifically recited by those in the West who even concede its occurrence. In Ukraine, collectivization was completed long before the Central Statistical Office ceased publication. Long before doctors were forbidden to record deaths as due to starvation. Long before holod, the Ukrainian word for famine, was outlawed. Long before the Ukrainian-Russian border was sealed, preventing anyone from leaving Ukraine for Russia in search of food. Ukrainian villages starved. Russian villages a few hundred yards across the border did not.

The ensuing half-century of worldwide silence testifies to the effectiveness of the Soviet disinformation effort on a global scale. Eugene Lyons wrote bitterly that “the most rigorous censorship in all of Soviet Russia’s history has been successful. It had concealed the catastrophe, until it was ended, thereby bringing confusion, doubt, contradiction into the whole subject.” Concurrently, the Soviet Union achieved its greatest foreign-policy goals–America extended diplomatic recognition and the international community invited it to join the League of Nations.

Soviet brutality has never been exploited by its enemies as a way of undermining Soviet power. Indeed, its brutalities have increased its might, helping to transform it into a global superpower. “The Soviet Union is not only the original killer state, but the model one,” wrote Nick Eberstadt of the Harvard Center for Population Studies.

For American newsmakers, such an image remains awkward, untimely, impolitic, inexpedient. Yet the man-made famine in Ukraine represents, as much as any one event can, the USSR’s most precarious fault lines, domestically and globally.

****

It is no wonder that several years later, this socialist dream of population control disintegrated in a collapse of its own lies and contradictions.

The wonder is that the murderous socialist charade lasted as long as it did.

What do we say to the millions of souls who perished?