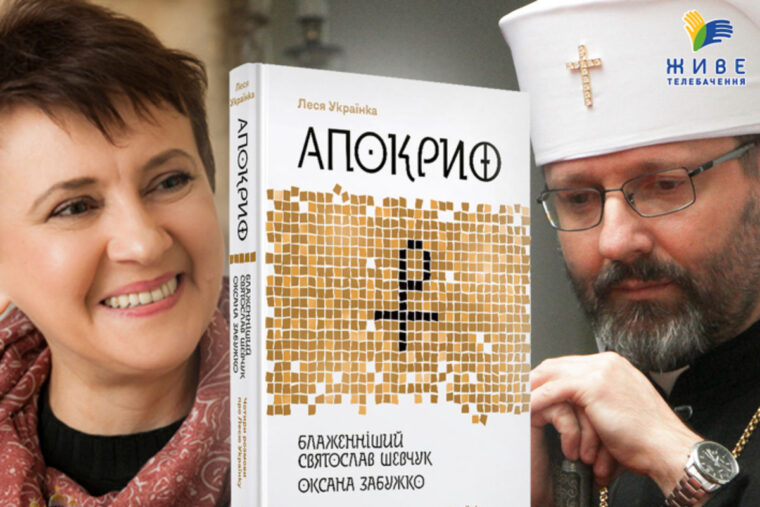

The majority of the writings published in Apocryphal: Four Conversations About Lesya Ukrainka (Kyiv: Komora Publishing House, 2020, 627 pp.) were written in the last decade of Ukrainka’s life, characterized, as Oksana Zabuzhko explains,“by a continual spiritual quest, even to say a search for her religion…” Hanna Hadzhylova, writing in her academic introduction explaining what version of original texts were included in this publication, explains that “the question of Christianity preoccupied Lesya Ukrainka… in the context of its influence on the future of humanity in general and on her native Ukraine in particular.”Hadzhylova’s insight is that virtually every self-sacrificing hero inUkrainka’s dramas “is motivated by Love…Such is Lesya’s path to recognizing eternal Truth.”

True martyrdom, especially female martyrdom, recurs in Ukrainka’s dramatic poems. Patriarch Sviatoslav explains that just as Jesus receives a delegated authority from God the Father, the Church has a role in tempering what could appear as enthusiasm for martyrdom. He elaborates on martyrdom as a gift from God that can be received but never manufactured. “Martyrdom for the sake of shedding blood is not enough…The Christian martyr makes visible and present the risen Christ. He is a witness to His strength, His victory…”

He adds that the martyrs “were unique intermediaries between the earthly and heavenly Church… with their own ministry of service and diakonia…” On this theme, Oksana Zabuzhko refers to Ukrainka’s play about Rufus and Priscilla “where they are in prison and give their blessing to those who have come to see them, because they are condemned to death” and now possess this charism.

The character of Judas Iscariot is discussed at length. In “Na polikrovi” “On the field of blood” Ukrainka questions why Jesus didnot see the real Judas. Commenting on the text, His Beatitude explains that Jesus is portrayed as a provocateur, continually “challenging one to reassess the framework for how you comprehend your life, a provocateur after whom to follow- and very often it’s the case that he’s leading you somewhere other than you thought at the beginning.”

At the end of “Na polikrovi” a stone is thrown at Judas by one of his main interlocutors. But the stone falls short. A well-known artistic director, Iryna Volytska, once remarked to Oksana Zabushko that this gesture is for her the key to interpreting the entire play. In response, the Patriarch notes thatthe manner in which Ukrainka concludes the play was a “stroke of genius” and a call to the audience “to make an examination of conscience.”

Zabuzhko makes several references to the relevance of Ukrainka’s writing in our day and age, including a comment from a Ukrainian woman she had once interviewed. The elderly woman had been in the patrioticand nationalist movement of the Second World War and said it was as though she too were living in the catacombs as Ukrainka describes them. About theMaidan protests of 2014, culminating in the shedding of blood of the great number of people now known as the Heavenly Hundred, Zabuzhkoasks how “God can be recognized through suffering.” She quotes Ukrainian poet Pavlo Tychyna (1891-1967): “And when the Lord revealed himself / in the blood of my brothers” and how those deaths by the Berkut police made of them a “martyr’s sacrifice”.

Several references are also made in the conversations to “Three Moments”- “Try Khvylyny”, a dramatic play from the same time period of Ukrainka’s life covered in Apokryf, although not included with the texts. It is set during the French Revolution rather than thehistorical period of early Christianity. Thematically, however, it does belong with the plays that address true martyrdom. As Zabuzhko explains, “one (character) saves his political opponent from death for the sole purpose of not allowing him to die as a martyr, because that type of death would give him great strength: ‘Power is not found, / in an idea, my Lord,but in blood itself’, in that sacrifice made upon an altar…”Mykhailo Kheifets, a fellow dissident with the Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus (1938-1985), commentedin Vasyl Stus: His Life and Works, Recollections and Essays by His Contemporaries, that Stus recommended this drama as an introductionUkrainka’s writings and he found it to be brilliant.

His Beatitude Sviatoslav summarizes Ukrainka’s faith by stating that sheis a Christian apologist, not for belief expressed cerebrally, but rather “a living experience of the divine… For Lesya Ukrainka, Christ is not an idea but a person.”

«… життя Лесі Українки, принаймні останні 12 років, це такі постійні духовно-релігійні пошуки –сказати б пошук своєї релігії. Починаючи від «Одержимої», ба навіть раніше – «Блакитна троянда», це ж теж пошук героями, сучасниками авторки, якогось свого віровизнавчого кредо поза межами офіційної Церкви: «Якби я була релігіозна, я пішла б в монастир, а то для таких як я, навіть монастирів нема», – каже головна героїня…» (Оксана Забужко).

«… в постаті Лесі Українки ми маємо справу з дуже особливою душею… Це є страждаюча особа, особа, яка шукає сенс у своїх власних екзистенційних стражданнях: і фізичних, і духовних, і інтелектуальних, і скажемо так, національних. Може, в тому появляється й той особливий жіночий погляд на драму людської екзистенції…» (Блаженніший Святослав Шевчук).

Article and translations by Fr. Jeffrey D. Stephaniuk

Photo: Zhyve tv www.synod.ugcc.ua