Arguably one of Ukraine’s most famous Easter traditions is their intricately decorated Easter eggs known as ‘pysanka’. The word pysanka comes from the verb pysaty, “to write”. Creating pysanka is an extremely complicated endeavor and they are usually created during the last week of Lent. The smoothest and best-shaped eggs are used to make pysanka. A stylus is often used to ensure and perfect the clean lines and intricate patterns on the eggs. Pysanka are given to friends and loved ones to represent the gift of life, and are usually decorated to match the personality of the receiver.

One of the most popular; and oldest, pysanky legends tells of a young woman who was on her way home from the market in town. She had with her a jug of fresh water for her journey and a basket of eggs. On her way she met a stranger sitting on a rock. Thinking he must be a tired traveler, she offered him a drink of her water. When he handed the water back to her, she was surprised to see that he had wounds on his hands. The stranger said nothing, but got up and went in the opposite direction of the young woman. When she arrived home, she uncovered her basket and discovered her eggs had been turned into beautiful pysanky The stranger, of course, had been Jesus Christ, and that was the first Easter morning.

Simply put, it is an Easter egg decorated using a wax resist (aka batik) method. Its name derives from the Ukrainian verb “pysaty,” meaning “to write.” (“Pysanka” is the singular form; “pysanky” is plural.)

But it is much more than that. Ukrainians have been decorating eggs, creating these miniature jewels, for countless generations. There is a ritualistic element involved, magical thinking, a calling out to the gods and goddesses for health, fertility, love, and wealth. There is a yearning for eternity, for the sun and stars, for whatever gods that may be.

The design motifs on pysanky date back to pre-Christian times–many date to early Slavic cultures, while some harken to the days of the Trypillians, my neolithic ancestors, others to paleolithic times. While the symbols have remained through the ages, their interpretation has changed, in an act of religious syncretism. A triangle that once spoke of the three elements, earth, fire and air, now celebrates the Christian Holy Trinity. The cross which depicted the rising sun is now the symbol of the risen Christ. Sun and star symbols once referred to Dazhboh, the sun god, and now refer to the one Christian God. And the fish, which spoke of a plentiful catch and a full stomach, now stands in for Christ, the fisher of men. Even so, under this Christian veneer, there still lurk the berehynia and the serpent, the sun and the moon, the old gods, the old ways, and the old beliefs.

Pysanka Traditions

In the countless centuries that Ukrainians have been creating pysanky, many traditions have grown up around their creation, sharing, and talismanic uses.

The customs described here were followed closely throughout Ukraine in the pre-Modern era, i.e. up until perhaps the mid-19th century, and continued to be practiced in some regions until after WWII. They are rarely practiced today in their original forms, although some continue to be honored in Ukrainian villages.

Why did these traditions change?

With the coming of science and technology and a more modern world, folk life began to change, as beliefs in magic and the supernatural diminished. The old ways were viewed as mere superstition, and were either forgotten, or followed in part, even as their talismanic and supernatural underpinnings were forgotten. Most people simply no longer believed in demons and evil spirits, nor in the magical properties of eggs.

Another factor pushing change was the commercialization in the 1800s of pysankarstvo in some regions of Ukraine. While most people continued to create pysanky for their own use, others began creating them for sale, not just to neighbors, but also for markets in neighboring cities and countries. Foremost among the commercial pysankary were the Hutsuls, who sold their wares in Ukraine and in nearby areas of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

In the twentieth century, in eastern and southern Ukraine, religion and national identity were suppressed as formal policy by the USSR. Pysankarstvo died out in many regions altogether, as it was viewed as a religious practice, unlike folk painting, embroidery and woodworking, which were not only allowed to continue to be practiced, but were actively commercialized and mechanized. (After WWII, when the USSR annexed western Ukraine as well, similar suppression of pysankarstvo and Ukrainian identity occurred there as well.)

And, most recently, pysankarstvo has been fully transformed into both a folk and fine art. Modern tools and dyes have taken over, and few people remember how to create traditional pysanky, much less the rituals involved with their creation. While a revival of the folk pysanka is occurring in Ukraine, many artists have taken up pysankarstvo and are creating beautiful, albeit miniature, works of pysanka art.

Symbolism in pysanky

A great variety of ornamental motifs are found on pysanky. Because of the egg’s fragility, few ancient examples of pysanky have survived. However, similar design motifs occur in pottery, woodwork, metalwork, Ukrainian embroidery and other folk arts, many of which have survived.

A great variety of ornamental motifs are found on pysanky. Because of the egg’s fragility, few ancient examples of pysanky have survived. However, similar design motifs occur in pottery, woodwork, metalwork, Ukrainian embroidery and other folk arts, many of which have survived.

The symbols which decorated pysanky underwent a process of adaptation over time. In pre-Christian times these symbols imbued an egg with magical powers to ward off evil spirits, banish winter, guarantee a good harvest and bring a person good luck. After 988, when Christianity became the state religion of Ukraine, the interpretation of many of the symbols began to change, and the pagan motifs were reinterpreted in a Christian light.

Since the mid-19th century, pysanky have been created more for decorative reasons than for the purposes of magic, especially among the Diaspora, as belief in most such rituals and practices has fallen by the wayside in a more modern, scientific era. Additionally, the Ukrainian diaspora has reinterpreted meanings and created their own new symbols and interpretations of older ones.

The names and meaning of various symbols and design elements vary from region to region, and even from village to village. Similar symbols can have totally different interpretations in different places. There are several thousand different motifs in Ukrainian folk designs. They can be grouped into several families. Keep in mind that these talismanic meanings applied to traditional folk pysanky with traditional designs, not to modern original creations.

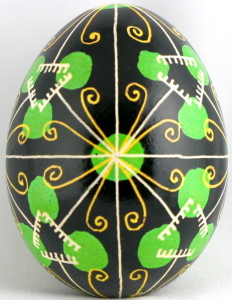

Geometric

The most popular pysanka designs are geometric figures. The egg itself is most often divided by straight lines into squares, triangles and other shapes. These shapes are then filled with other forms and designs. These are also among the most ancient symbols, with the решето (resheto, sieve) motif dating back to Paleolithic times. Other ancient geometric symbols are agricultural in nature: triangles, which symbolized clouds or rain; quadrilaterals, especially those with a resheto design in them, symbolized a ploughed field; dots stood for seeds.

Geometric symbols used quite commonly on pysanky today. The triangle is said to symbolize the Holy Trinity; in ancient times it symbolized other trinities: the elements of air, fire and water, the family (man, woman and child) or the cycle of life (birth, life, and death). Diamonds, a type of quadrilateral, are sometimes said to symbolize knowledge. Curls/spirals are ancient symbols of the Zmiya/Serpent, and are said to have a meaning of defense or protection. The spiral is said to be protective against the “нечиста сила”; an evil spirit which happens to enter a house will be drawn into the spiral and trapped there. Dots, which can represent seeds, stars or cuckoo birds’ eggs (a symbol of spring), are popularly said to be the tears of the blessed Virgin. Hearts are also sometimes seen, and, as in other cultures, they represent love.

Eternity bands

Eternity bands or meanders are composed of waves, lines or ribbons; such a line is called a “bezkonechnyk.” A line without end is said to represent immortality. Waves, however, are a water symbol, and thus a symbol of the Zmiya/Serpent, the ancient water god. Waves are therefore considered an agricultural symbol, because it is rain that ensures good crops.

Berehynia

Berehynia

The goddess motif is an ancient one, and most commonly found in pysanky from Polissia or Western Podillia. The berehynia was believed to be the source of life and death. On the one hand, she is a life giving mother, the creator of heaven and all living things, and the mistress of heavenly water (rain), upon which the world relies for fertility and fruitfulness. On the other hand, she was the merciless controller of destinies.

he most common depiction of the great goddess is a composition containing “kucheri” (curls). The berehynia may be seen perched on a curl, or a curl may be given wings. Often there is a crown on the berehynia’s head. These compositions are given the folk names of “queen,” “princess,” “scythe,” “drake,” or simply “wings.”

Christian symbols

The only true traditional Christian symbol, and not one adapted from an earlier pagan one, is the church. Stylized churches are often found on pysanky from western Ukraine, particularly those in the Hutsul regions and Bukovyna; a sieve motif inside is said to symbolize the church’s ability to separate good from evil.

The only true traditional Christian symbol, and not one adapted from an earlier pagan one, is the church. Stylized churches are often found on pysanky from western Ukraine, particularly those in the Hutsul regions and Bukovyna; a sieve motif inside is said to symbolize the church’s ability to separate good from evil.

Crosses are fairly common, although most of those found on traditional pysanky are not Ukrainian (Byzantine) crosses. The crosses most commonly depicted are of the simple “Greek” cross type, with arms of equal lengths. This type of cross predates Christianity, and is a sun symbol (an abstracted representation of the solar bird); it is sometimes combined with the star (ruzha) motif. The “cross crosslet” type of cross, one in which the ends of each arm are crossed, is frequently seen, particularly on Hutsul and Bukovynian pysanky.

Other adapted religious symbols include a triangle with a circle in the center, denoting the eye of God, and one known as the “hand of god.”

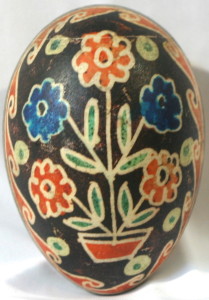

Phytomorphic (Plant) motifs

The most common motifs found on pysanky are those associated with plants and their parts (flowers and fruit). Women who wrote pysanky drew their inspiration from the world of nature, depicting flowers, trees, fruits, leaves and whole plants in a highly stylized (not realistic) fashion. Such ornaments symbolized the rebirth of nature after winter, and pysanky were written with plant motifs to guarantee a good harvest. A most popular floral design is a plant in a vase of standing on its own, which symbolized the tree of life and was a highly abstracted version of the berehynia (great goddess).

Pysanky created by the mountain people of the Hutsul region of Ukraine often showed a stylized fir tree branch, a symbol of youth and eternal life. Trees, in general, symbolized strength, renewal, creation, growth; as with animal motifs, the parts (leaves, branches) had the same symbolic meaning as the whole. The oak tree was a sacred to the ancient god Perun, the most powerful of the pagan Slavic pantheon, and thus oak leaves symbolized strength.

Pussy willow branches are sometimes depicted on pysanky; in Ukraine, the pussy willow replaces the palm leaf on Palm Sunday. This is not a common motif, though, and may be a more recent addition.

Flowers

Flowers are a common pysanka motif. They can be divided into two types: specific botanical types, and non-specific.

Specific botanical types include sunflowers, daisies, violets, carnations, periwinkle and lily-of the-valley. These flowers are represented with identifying features that make them recognizable. Carnations will have a serrated edge to the petals, the flowers of the lily of the valley will be arrayed along a stem, periwinkle will have three or four leaves (periwinkle is represented by its leaves, not its flowers, on pysanky).

Vazon/Tree of Life

Vazon/Tree of Life

The “tree of life” motif is widely used in traditional pysanky designs. It can be represented in many ways. Sometimes it appears as two deer on either side of a pine tree. More often it manifests as a flower pot (“vazon”), filled with leaves and flowers. The pot itself is usually a rectangle, triangle or a rhomboid (symbolic of the earth), and is covered with dots (seeds) and dashes (water). Many branches grow out of it, in a symmetric fashion, with leaves and flowers. This plant is a berehynia (goddess) symbol, with the branches representing the many arms of the mother goddess.

Fruit

Fruit is not a common motif on pysanky, but is sometimes represented. Apples, plums and cherries are depicted on traditional pysanky. Currants and viburnum (kalyna) berries are sometimes seen, too. These motifs are probably related to fecundity. Grapes are seen more often, as they have been transformed from an agricultural motif to a religious one, representing the Holy Communion.

Scevomorphic motifs

Scevomorphic designs are the second-largest group of designs, and are representations of man-made agricultural objects. These symbols are very common, as Ukraine was a highly agricultural society, and drew many of its positive images from field and farm. Some of these symbols are actually related to agriculture; others have older meanings, but were renamed in more recent times based on their appearance.

Common symbols include the ladder (symbolizing prayers going up to heaven) and the sieve/resheto (a plowed field, or perhaps the separation of good and evil).

Zoomorphic (Animal) motifs

Although animal motifs are not as popular as plant motifs, they are nevertheless found on pysanky, especially those of the people of the Carpathian Mountains. Animal depicted on pysanky include both wild animals (deer, birds, fish) and domesticated ones (rams, horses, poultry). As with plants, animals were depicted in the abstract, highly stylized, and not with realistic detail.

Although animal motifs are not as popular as plant motifs, they are nevertheless found on pysanky, especially those of the people of the Carpathian Mountains. Animal depicted on pysanky include both wild animals (deer, birds, fish) and domesticated ones (rams, horses, poultry). As with plants, animals were depicted in the abstract, highly stylized, and not with realistic detail.

Horses were popular ornaments because they symbolized strength and endurance, as well as wealth and prosperity. They also had a second meaning as a sun symbol: in some versions of pagan mythology, the sun was drawn across the sky by the steeds of Dazhboh, the sun god. Similarly, deer designs were very prevalent as they were intended to bring prosperity and long life; in other versions of the myth, it was the stag who carried the sun across the sky on his antlers. Rams are symbols of leadership, strength, dignity, and perseverance.

Birds

A traditional Ukrainian pysanka with bird motifs

Birds were considered the harbingers of spring, thus they were a commonplace pysanka motif. Birds of all kinds are the messengers of the sun and heaven. Birds are always shown perched, at rest, never flying (except for swallows and, in more recent times, white doves carrying letters). Roosters are symbols of masculinity, or the coming of dawn, and hens represent fertility.

Insects

Insects are only rarely depicted on pysanky. Spiders and, more often, their webs are the most common, and probably symbolize perseverance. Other insects are sometimes seen on modern, diasporan pysanky, most commonly butterflies and bees, but seem to be a modern innovation. In Onyshchuk’s “Symbolism of the Ukrainian Pysanka” she depicts pysanky with a butterfly motif, but the original design, recorded by Kulzhynsky in 1899, was labeled as being swallow tails.

Fish

The fish, originally a symbol of health, eventually came to symbolize Jesus Christ, the “fisher of men.” In old Ukrainian fairy tales, the fish often helped the hero to win his fight with evil. In the Greek alphabet “fish” (ichthys) is an acrostic of “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior,” and it became a secret symbol used by the early Christians. The fish represents abundance, as well as Christian interpretations of baptism, sacrifice, the powers of regeneration, and Christ himself.

Serpent

Another ancient symbol is that of the змія or serpent, the ancient god of water and earth. The serpent could be depicted in several ways: as an “S” or sigma, as a curl or spiral, or as a wave. When depicted as a sigma, the zmiya often wears a crown. Depictions of the serpent can be found on Neolithic Trypillian pottery. The serpent symbol on a pysanka is said to bring protection from catastrophe. Spirals were particularly strong talismans, as an evil spirit, upon entering the house, would be drawn into the spiral and trapped there.

Cosmomorphic motifs

Among the oldest and most important symbols of pysanky is the sun, and the simplest rendering of the sun is a closed circle with or without rays. Pysanky from all regions of Ukraine depict an eight-sided star, the most common depiction of the sun; this symbol is also called a “ruzha.” Six- or seven-sided stars can also be seen, but much less commonly.

The sun can also appear as a flower or a трилист (three leaf). Called in Ukrainian a “svarha,” is sometimes referred to as a “broken cross” or “ducks’ necks.” It represented the sun in pagan times: the movement of the arms around the cross represented the movement of the sun across the sky. The Slavic pagans also believed that the sun did not rise on its own, but was carried across the sky by a stag (or, in some versions, a horse). The deer and horses often found on Hutsul pysanky are solar symbols.

Pysanky with sun motifs were said to have been especially powerful, because they could protect their owner from sickness, bad luck and the evil eye. In Christian times the sun symbol is said to represent life, warmth, and the love and the Christian God.

Color symbolism

It is not only motifs on pysanky which carried symbolic weight: colors also had significance. Although the earliest pysanky were often simply two-toned, and many folk designs still are, some believed that the more colors there were on a decorated egg, the more magical power it held. A multi-colored egg could thus bring its owner better luck and a better fate.

The color palette of traditional pysanky was fairly limited, and based on natural dyes. Yellow, red/orange, green, brown and black were the predominant colors. With the advent of aniline dyes in the 1800s, small amounts of blue and purple were sometimes added. It is important to note that the meanings below are generalizations; different regions interpreted colors differently.

- Red – is probably the oldest symbolic color, and has many meanings. It represents life-giving blood, and often appears on pysanky with nocturnal and heavenly symbols. It represents love and joy, and the hope of marriage. It is also associated with the sun.

- Black – is a particularly sacred color, and is most commonly associated with the “other world,” but not in a negative sense.

- Yellow – symbolized the moon and stars and also, agriculturally, the harvest.

- Blue – Represented blue skies or the air, and good health.

- White – Signified purity, birth, light, rejoicing, virginity.

- Green – the color of new life in the spring. Green represents the resurrection of nature, and the riches of vegetation.

- Brown – represents the earth.

Some color combinations had specific meanings, too:

- Black and white – mourning, respect for the souls of the dead.

- Black and red – this combination was perceived as “harsh and frightful,” and very disturbing. It is common in Podillya, where both serpent motifs and goddess motifs were written with this combination.

- Four or more colors – the family’s happiness, prosperity, love, health and achievements.

As with symbols, these talismanic meanings of colors applied to traditional pysanky with traditional designs, and not to modern decorative pysanky.